We must end the current Petrobrás pricing policy and stop its privatization

For cheap fuel and cooking gas, the practice of following international market prices must stop

Publicado em: 2 de março de 2021

We are in one of the biggest economic crises in the history of capitalism. Over 14 million people are already unemployed across the country, and emergency aid, the only source of income for millions of Brazilians, is now coming to an end. Amidst all this, we are also seeing a crisis in the liberal policies of the Bolsonaro government. It is difficult to tell the population that they should pay more for fuel and cooking gas just to keep the “market” satisfied. An indication of this is the recent resignation of Petrobrás president, Roberto Castello Branco, one of the most enthusiastic advocates for the destruction of Petrobrás and handing it over to private and foreign capital. Despite Bolsonaro’s ranting about being on the side of the people, who want lower prices, we see no signs that the core of the current economic policies that cause excessive price rises will change. In 2018, the then president of Petrobrás, Pedro Parente, was also removed from the state-owned company after a strike by truck and oil tanker drivers. But this was not a real change, just a temporary, cosmetic touch-up.

In this article, we aim to demonstrate that the only way to ensure affordable prices is through the reversal of the process of the privatization of Petrobrás that has only benefited foreigners and companies linked to Minister of the Economy Paulo Guedes. We will analyze how the prices of petroleum products – gasoline, diesel, and cooking gas – have reached such exorbitant prices, and point to the need to end the so-called Import Parity Price (IPP). To defend Petrobrás is to defend our economy, the economy for the workers, not for a handful of shareholders.

Why are fuel and cooking gas prices so high and excessive?

In Brazil, cooking gas, gasoline, and diesel prices follow a Petrobrás pricing policy implemented by Michel Temer and Pedro Parente in 2016, a policy called Import Parity Price (IPP). The prices of petroleum and natural gas products “are based on the import parity price, formed by the international prices for these products plus the costs that importers would have, such as transportation and port levies, for example.” (1) It’s as if the price of these items were the same as prevailing international market prices, plus the cost of bringing them to our gas station or gas retailer, and all this in US Dollars!

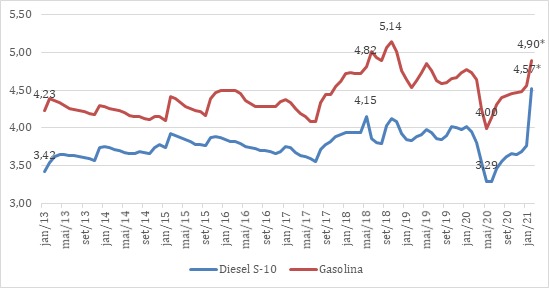

This value is largely determined by the price of oil, that is, the value of Brent Crude Oil (a type of oil, and the commodity’s main international price benchmark). Brent Crude traded at less than US$30 a barrel between March and May 2020 in the wake of the crisis that hit the sector at the start of the pandemic. Today it has already exceeded US$62 and is trending upward, a trend that has intensified with the beginning of vaccinations around the globe. According to estimates by Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan, we may be living through a new petroleum price supercycle that will cause the price of petroleum to reach values between US$80 and 100 dollars (2) – which will push fuel and LPG prices even higher.

Graph 1 – Average daily Brent price in US dollars (in current values)

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

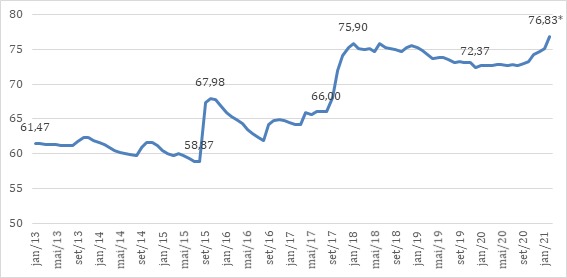

The consequence of this Petrobrás policy is large price increases. With the rise in the price of a barrel of oil and the devaluation of the US dollar, this system of pricing causes values to jump, as we can see in the next two graphs. In the first one we see the real increase (taking inflation into account, so that the data is more “comparable”) over these last months. The price of diesel recently reached a historic record, and the same feat is looming for the price of gasoline. It is important to point out that the highest previous prices occurred during the truck drivers’ strike in May 2018. While diesel has seen a small price fall after a policy exemption by then-President Temer (implemented to bring the strike to an end), gasoline prices still continued to rise until October of that year, when a period of large falls in the international oil price began.

Graph 2 – Price of Diesel S-10 and Regular Gasoline at the retailers in real values as of December 2020 (February is an estimate)

Source: National Petroleum Agency (ANP); Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) [Our compilation].

This disastrous pricing policy is dramatically expressed in cooking gas prices, which are already higher than the previous record set at the start of 2018. Unlike gasoline and diesel, LPG did not see a price reduction during the pandemic, as the demand for gas increased as people started to cook much more at home. According to the Brazilian Association of Liquefied Gas Dealers (ASMIRG), the price of a 13kg cylinder may reach R$150 (US$26.50) by 2021 (3) – a national tragedy.

Graph 3 – Retail LPG price in December 2020 real terms (February is an estimate)

Source: National Petroleum Agency (ANP); Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) [Our compilation].

As the data shows, the drastic price increases for these derivatives are determined by international oil prices, which pollute our country through the IPP parity system.

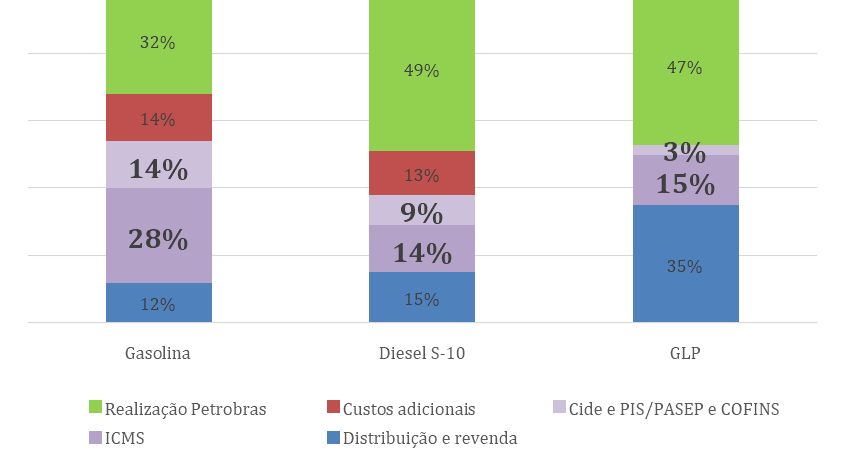

Does removing taxes work? Does it make sense?

Bolsonaro is betting on the same strategy as always, placing the blame on others. To do so, he takes advantage of the timeless ‘common sense’ approach of blaming taxes. As we can see in Graph 4, taxes are only a part of the final price of these items. Gasoline is the only one of these products in which tax makes up a large portion of the price, 42% between the state Tax on the Circulation of Goods and Services (ICMS) and federal taxes. The Diesel price includes 23% state and federal taxes. For cooking gas, this tax figure is only 18%.

Compared to European countries, we have much lower taxes. France, Germany, Italy, and Britain have a tax burden of 58% on diesel, 63% on gasoline, and 34% on LPG, due to environmental policies and policies that discourage individual transport. In the United States, a country with a lower tax burden on consumption (due to a higher concentration of tax on income and wealth), taxes on both diesel and gasoline stand at just 21%.

Graph 4 – The formation of prices for each oil derivative

Gasoline / Diesel S-10 / LPG

* Price established by Petrobrás

* Additional costs

* Federal taxes (CIDE, PIS/PASEP and COFINS)

* The state Tax on the Circulation of Goods and Services (ICMS)

* Distribution and resale

Source: Petrobrás

The policy of dropping the federal tax component on these products to zero has only a small effect – just remember that since the beginning of the year the accumulated price rise for diesel is 27%, nine times its federal tax burden, for example. According to estimates from the Brazilian Association of LPG Retailers (ABRAGÁS), eliminating federal taxes on LPG will see a reduction of only R$2.18 (US$0.40) per cylinder (4), and ABRAGÁS suggests that there is not even a guarantee that the R$2 will reach the final consumer. But the bill is high. Estimates by XP Investimentos for diesel exemptions say that this policy will remove R$3 billion (US$0.55 billion) from federal coffers every two months – that is, a loss of R$18 billion (US$3.2 billion) to the budget if this change becomes permanent. In a country where federal revenues fell by 6.91% in 2020, this seems like suicide. Apart from all this, we know that someone will end up paying the bill, and with this government, those who pay the bill are never the ones who really should. They will more than likely demand the need for new reforms, such as the Administrative Reform, that would reduce the already flattened salaries of the public service and take away even more of their rights.

Privatization makes the situation worse

The policy of privatization is demonstrating its results. For example, the privatization of Liquigás, a formerly state-owned company that resells and distributes cooking gas, and the resulting formation of a private oligopoly in that sector, has reduced the government’s power to prevent excessive prices for cooking gas. As we can see in Graph 4, these companies capture 35% of the final price paid for the product.

The sale of oil refineries will be a death blow for the people of Brazil. If Petrobrás management and the Bolsonaro government manage to sell half of the country’s refining capacity – as they plan to do this year and the next – we will have no option but to accept excessive prices which are much higher than the real costs of these refined products. The handing over of refineries in Paraná, Pernambuco, Minas Gerais, and the rest of the country, will create regional private monopolies. Who will say how much gasoline will cost in Bahia when it belongs to the Mubadala Investment Company, an investment fund wholly-owned by an Arab Emirates government. In Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina, the Igel family from the Ultra group, are the most likely buyers of the Alberto Pasqualini refinery (REFAP).

Bring the international price parity and the program of privatization to an end!

The figures demonstrate that the only real determinant behind the explosion of fuel and cooking gas prices is the IPP. This is why we will only solve the problem if we manage to end this policy once and for all. This would not damage Petrobrás in any way, in fact just the opposite. We want to strengthen the state-owned company, make it grow with more refineries, and produce more biofuels and gas. We are not the ones handing over refineries, gas pipelines, oil wells, and an infinite number of other very valuable assets to the market. If Petrobrás continues down this road, along with losing control over energy transition in Brazil, a role in which our state-owned company has always played a unique role, we will have to accept all the dictates of the market.

When most workers are unable to buy gas to cook at home, when delivery workers, app drivers, and truck drivers are no longer able to work, when more and more people are walking because of the high price of public transport, the words of Roberto Castello Branco’s will become the norm: “I raise the price here, I have nothing to do with a truck driver”.

To defend Petrobrás is to defend popular sovereignty and economic planning, and not the dictatorship of the market!

Bring IPP to an end! Oppose the sale of the refineries!

NOTES

1. “Gasolina e Diesel” (Gasoline and Diesel), Petrobrás website,

https://Petrobrás.com.br/pt/

2. David Sheppard, “Oil ‘supercycle’ predictions divide veteran traders”, Financial Times, 16 February 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/

3. Tácio Lorran, “Revendedores de gás de cozinha estimam preço do botijão a R$ 150 ainda em 2021” (Cooking gas distributors project a bottled gas price of R$150 (US$26.50) by 2021), Metrópoles (Metropolises), 6 January 2021, https://www.metropoles.com/

4. Mariangela Castro, “Governo deve zerar imposto sobre gás de cozinha, mas redução será de apenas R$2” (Government to reduce tax on cooking gas to zero, but the reduction will only be R$2 (US$0.40), CNN Brasil, 19 February 2021, https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/

Source: OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin 2020.

*This article is an English translation of “É preciso acabar com a atual política de preços da Petrobrás e parar a privatização”, [https://esquerdaonline.com.

Top 5 da semana

mundo

Carta aberta ao presidente Lula sobre o genocídio do povo palestino e a necessidade de sanções ao estado de israel

editorial

É preciso travar a guerra cultural contra a extrema direita

marxismo

O enigma China

brasil

Paralisação total nesta quinta pode iniciar greve na Rede Municipal de Educação de BH

mundo

Para vencer, Lula precisa girar à esquerda

Para vencer, Lula precisa girar à esquerda